Call for entries: Deniz Villaları – Ecological Crossings

We’re delighted to announce our partnership with the Institut français de Turquie and the Goethe-Institut Türkei in their call for…

Published on 10 June 2020

COAL 2020 AWARD WINNING PROJECT

Paul Duncombe was born in 1987. He lives and works in Caen, France.

A graduate of the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, Paul Duncombe explores the different scales of landscape. His successive researches, on the Labrador ice floes, the storms in the Celtic Sea, the boreal forests, or the irradiated lands of Fukushima, put in relation the apparent simplicity of the works of nature with the increasing technicality of modern societies. From simple gestures to the most complex monumental installations, his work crosses borders and disciplines, relying on collaborations with specialists from all horizons: biologists, geologists, astrophysicists, high mountain guides…thus multiplying points of view and experiences. He develops and exhibits his projects in France: Le 104, 63e Salon de Montrouge, Palais de Tokyo, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac and abroad: Unicorn Center for Art (Beijing), Coopérative Méduse (Quebec), Kyoto Art Center (Kyoto).

MANICOUAGAN

Known as the Eye of Quebec, the Manicouagan impact crater is one of the largest and best preserved on Earth. With a diameter of 100 km, it was formed 214 million years ago following the fall of a meteorite of 8 km. Lost in the middle of Quebec, the Astroblème, now classified as a World Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO, is home to unique fauna, flora and geological features. The extraterrestrial origin of these reliefs, the indigenous history of the territory and the artificial engulfment of vast forests by the waters, give the site a mystical aura.

Paul Duncombe wishes to extend to Manicouagan his research work undertaken since 2015 in collaboration with naturalists and geologists, on the violence of mass extinctions and meteorite impacts. From physical and digital samples taken on site during an expedition in complete autonomy, accompanied by a multidisciplinary team, it will represent all the mechanisms that led to the re-conquest of the site by plants, insects and other living species, until the first nations. In the aesthetics of space exploration missions (real and fictitious), a home-made electronic station will be deployed in the crater. With the poetry inherent in the naivety of the artistic gaze in the face of observed creatures and natural phenomena, this creative laboratory will unfold in pursuit of the sublime, of contingent beauties and evidence of an absolute hidden in nature.

In the digital age, in a world that is now mapped, rationalized, and aware of its finitude, this device that is both technological and artisanal, digital and physical, at the crossroads of science, naturalism, survivalism, and “maker” cultures, will allow for the reinvention or reintroduction of meaning and links between the initial historical crisis, the biological rebirth of the site, and modern crises, present or future.

What was your first sensitive relationship with living things?

Observation, understanding and respect for living things are part of my education. It is an important cultural heritage. I am fortunate to have grown up close to nature, surrounded by all kinds of creatures, and that is still the case. As a sensitive and determining report, I think of concrete situations like the operations of removal of seabirds in Lorient in 1999/2000 with the LPO (League for the Protection of Birds). These experiences in my youth have certainly contributed to my current sensitivity: nature has become a space that can be defined by the anthropic phenomena that destroy it and I am looking for the aesthetic potential of this imbalance between contemporary industrial powers and the fragility of life; between a soiled feather and the 30,000 tons of an oil tanker, to illustrate the previous example. There is a part of sublime in these deleterious relations of forces, between humanity and nature, between civilization and the living.

How did your interest in meteorite impacts on living things come about?

You have to imagine a projectile of several kilometers crossing the atmosphere in hardly a blink of an eye. The instantaneous liquefaction of the rock over a depth of 10,000 meters. A thick column of matter that rises to the stratosphere, then envelops the entire planet. Earthquakes of magnitude 12, devastating tidal waves, volcanic irruptions, fire storms, widespread fires… and in this chaos, life, which collides violently with matter.

When one is interested in the cosmos, it is less a question of the fragility of the living than of its absurdity. The history of the universe is that of a series of disproportionate catastrophes and certain scars on the surface of the Earth remind us that we are passing through this story made of celestial trajectories, molten matter and particles. The beauty of what surrounds us comes from there, from this staggering drift, from the contingency of events and the finitude of the living in this mineral eternity. Here too I am interested in the imbalance between these different forces and the resilience of animal or plant species. An astrobleme is an open-air museum, a memorial that speaks of the end of the world but also of the beginning again.

How did you discover the Manicouagan astrobleme?

During a 2015 residency in Quebec, I went to the North Shore, to Labrador, initially about “Iceberg Alley”. There is only one trail through the forest and it leads to the Manicouagan astrobleme. For an average human, the horizon is about 5km away and this crater is 100km away. It is there that I took the full measure of this incredible violence and its supposed repercussions on the living, on a local and then planetary scale. These broken landscapes actually reveal the true identity of the world and the creatures that inhabit it. Something absolute, like an implacable mechanic of fall, of gravity against which the upward momentum of life is in perpetual resistance. Staying at the Uapishka science station, I began to document and interact with scientists working at the site. This started a series of projects on biological crises: Triassic-Jurassic, Cretaceous-Paleogene, until today the so-called Holocene extinction.

What is your relationship with science fiction?

Whatever their nature, the imaginary worlds developed in cinematographic or literary works, or even video games, are only the reflection of our present. In the current abundance of futuristic dystopias, whether technological or political, there is undoubtedly a self-fulfilling prophecy. In my opinion, we are already in the middle of science fiction, we live it every day. It is therefore a major influence in my artistic work.

What is your environmental commitment as an artist and citizen?

Nature is also a political space and I have sometimes been involved in more militant environmentalist actions. But I think today that the real commitment is sobriety. This is a particularly difficult goal to achieve. In the meantime, I am extremely attached to rurality. This proximity to the field and to the people who live it on a daily basis allows me to get involved in all kinds of projects, to be in the experience, the practice and the concrete, in something that resembles reality.

How do you imagine the world to come?

Nature does not need to be saved, it is humanity that is in danger: we live in an outdated model, in illusion and torpor. “Another end of the world is possible” this contemporary adage could become a principle of shared popular action, a program of existence: we must reinvent our relationship to the world, to nature, to the living, to the other, and I believe that artists are working on it!

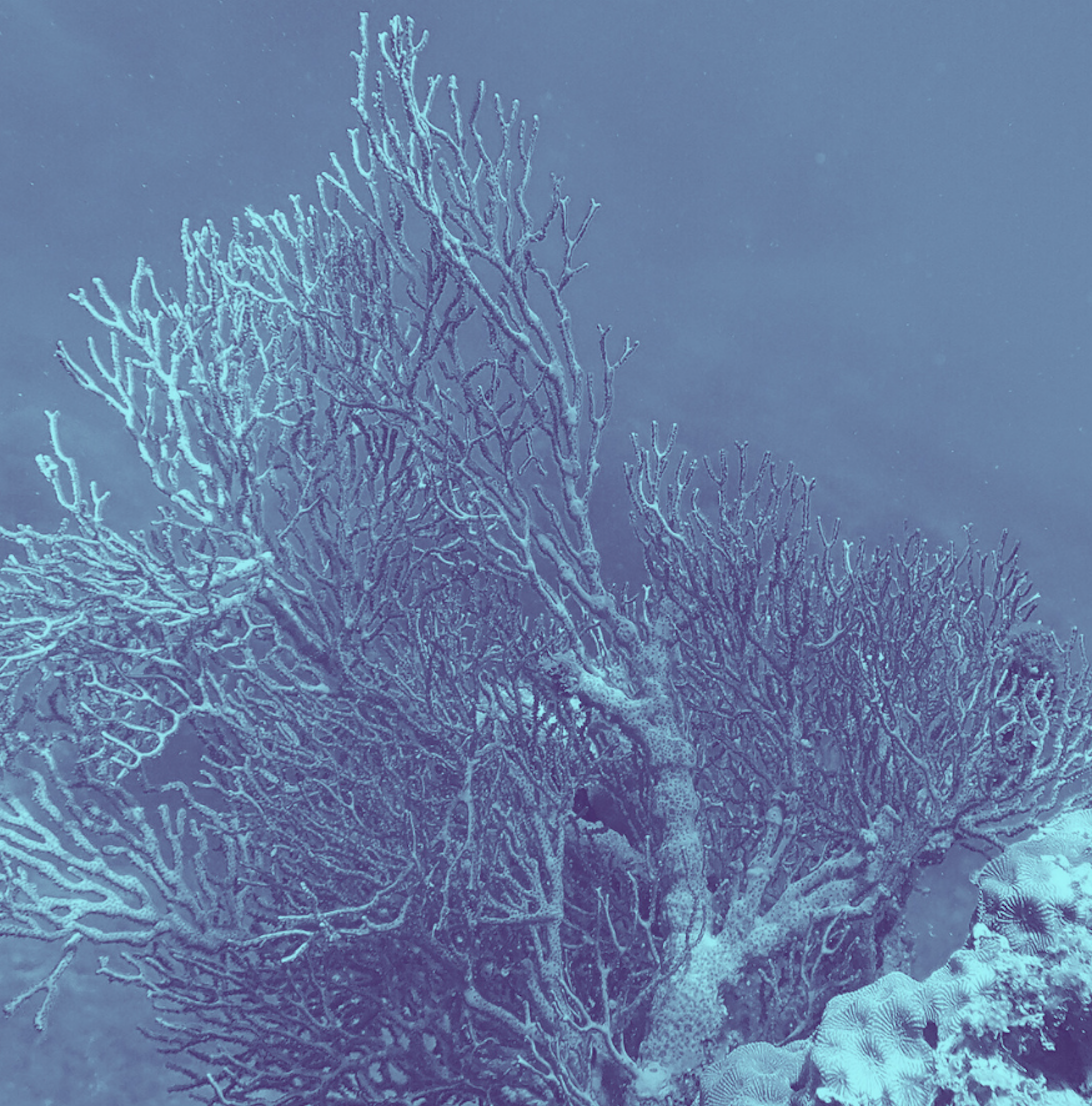

Featured image: Paul Duncombe, Quebec, 2015

We’re delighted to announce our partnership with the Institut français de Turquie and the Goethe-Institut Türkei in their call for…

Since 2022, as part of the Pays de l’Arbresle’s “Les murmures du Temps” art trail, Thierry Boutonnier has been sending…

Since 2022, as part of the Pays de l’Arbresle’s “Les murmures du Temps” art trail, Thierry Boutonnier has been sending…