CALL FOR PROJECTS COAL PRIZE 2025: Freshwater

The COAL Prize 2025 dedicated to fresh water is a call to fight against the drying up of our sensitivities…

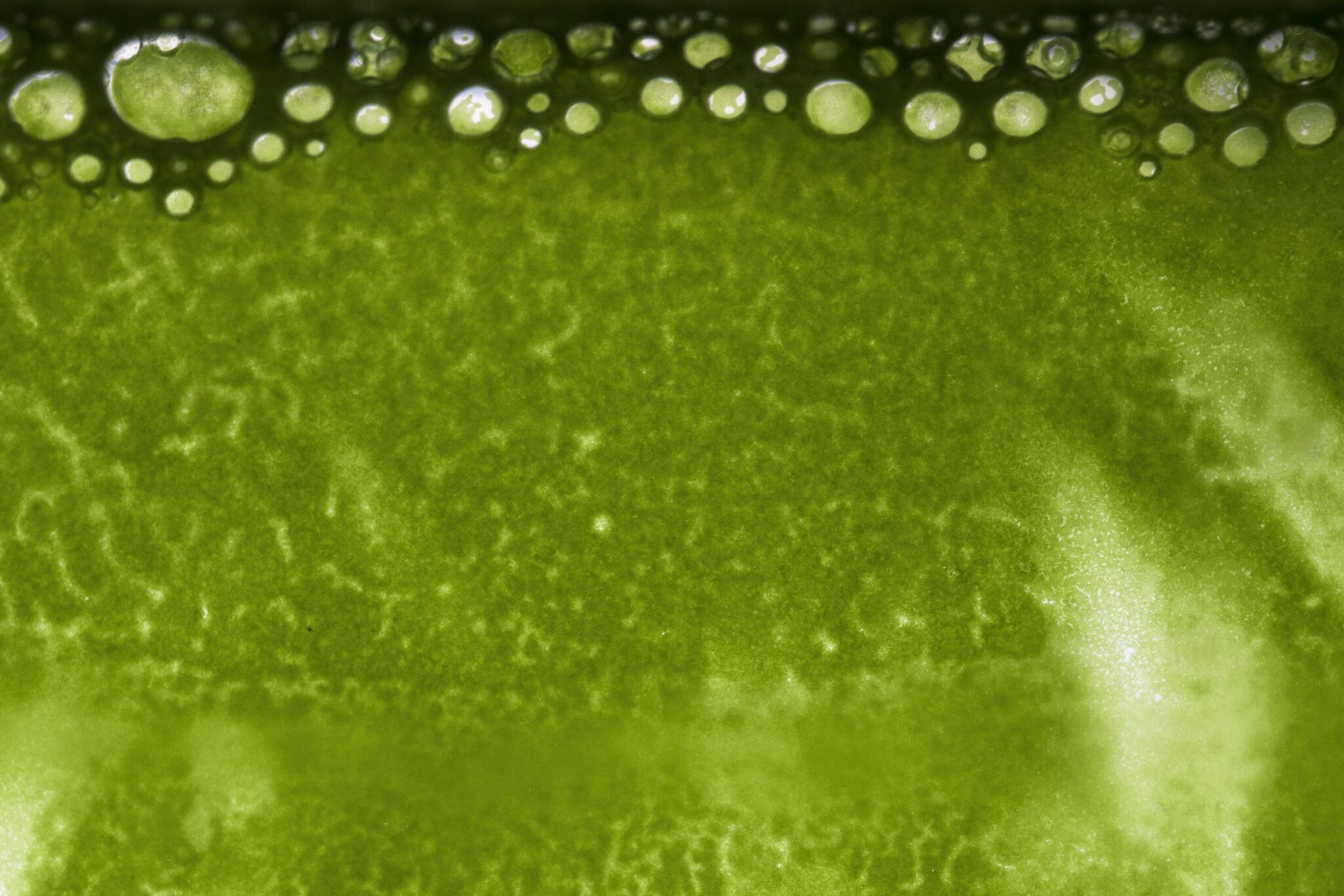

Image credits: © Lia Giraud, Ecoumène V.2, détail algaegraphique

Published on 8 June 2020

As part of the COAL 2020 Award, ten artists’ projects have been nominated as finalists for this eleventh edition. Each day, we offer you a meeting with one of the nominated projects.

Lia Giraud was born in 1985 in Paris, France. She lives and works in Paris, France.

Lia Giraud is an artist and a doctor in Visual Arts, trained in documentary image. For more than ten years, his installations have been questioning our conceptions and relationships to life, in a current context marked by science and technology. By making biological phenomena the sensitive and operative materials of her works, she highlights the states of rupture that agitate our experience of the “environment”. Committed to the creation of “new ecologies”, her works initiate interdisciplinary research ecosystems at the frontier of science and society, involving researchers in the natural sciences, thinkers, artists, and citizen communities. His work has been the subject of numerous exhibitions in France: Centre Pompidou, Le 104, Le Cube, Le Bel Ordinaire, and abroad: Festival Images de Vevey (Switzerland), Parc Naturel de l’Our (Luxembourg), Dutch Design Week (Netherlands), and educational interventions for the general public.

PROJECT NOMINATED FOR THE COAL 2020 AWARD: ECOUMENE

Since 2018, Lia Giraud has been exploring with Écoumène the habitability of territories reconfigured by human activities: the gentrification of Paris undermining its cultural diversity, or the disappearance of a Madagascan forest endangering existences at multiple scales. Everywhere, the rarefaction of life forms incites us to think about the impoverishment of the links and relations they initiate at multiple levels. This concrete disappearance has sensitive and cultural repercussions on us that we must understand and reveal.

The third part ofEcoumene is set in a polluted area of Mexico, a 15 km long “Dead Zone” along the El Salto River, irrigated by the chemical waste of about 400 industrial companies. Its health impacts on the population and the surrounding biodiversity are extremely heavy. Nourished by scientific research on the purifying faculties of certain micro-algae capable of resisting, accumulating and removing heavy metals present in acidic aquatic environments, this project envisages the resurgence of the living as a concrete solution to water purification, but also as a creative support, allowing to connect damaged existences.

The artist has indeed developed a process of living image called Algaegraphy. The photosensitive micro-algae literally “develop” the image to which they are exposed and confer organic behaviors that echo the narrative of each territory. A symbol of environmental sensitivity and universality, a biomaterial prized by the technosciences, microalgae are here the invisible ecological revelators of our actions and their future. Lia Giraud will create a series of living images as a means of dialogue. The aim is to explore the notion of resilience by discussing the ways in which life can develop biologically, socially and symbolically in the context of ecological disaster.

Describe your current environment, how do you live this covid-19 era? How does this situation influence your artistic process?

Being confined to my home in Paris, this period is a bit familiar but mostly unheard of! Many new things are expressed, observed and questioned. For an artist working with the living, it is like a scenario that is written on a daily basis. I like to dream that an ecological way out is possible when nature reclaims its rights in our deserted urban spaces. I am fascinated by the circulation of the virus which reveals the multiple links that unite humans and non-humans. I question myself on this invisible force capable of weakening the capitalist system but also on our reaction of protection and distancing in front of a potential death. I also observe our adaptation to a virtual world and our paradoxical desire to reconnect with the primary life forms that populate our kitchens and gardens. Put in dormancy, I experiment like others, a form of minimal life by trying to detect the essential. This crisis also brings to the fore beautiful energies: a capacity to reinvent ourselves and to propose a different world, more social I hope. It is still too early to sort out or know what will stand the test of time, but this period is nonetheless prolific and surprising: alive!

What was your first sensitive relationship with living things?

It is rather an ontological sensitivity of the living. I find it again, in this period of confinement: to change and provoke change, to escape from stability and control, to be fragile and for this reason precious, to enter in relation… It is this infinite capacity to “put in movement” (e-motio in Latin) which is literally the object of my emotion and which, since always, binds me to the living. It is these same sensitive processes that work each of my installations. The world we live in seems to be governed by immutability, control, individualism, infallibility. To reveal another system of values, the one that constitutes us as living beings, seems to me urgent. In my work, I am more interested in neglected forms of life, whose size or temporality seem to escape our perceptions. This life that we have forgotten. Through it, I seek to highlight the primary behaviors of this matter of which we are also constituted: sensitivities to the environment, dynamics of adaptation, phenomena of collective elaboration or struggle, individual specificities, etc… It is these hidden realities, revealed in my works, which animate me and allow me to imagine differently the world which comes.

What inspired your project? How did your interest in the subject come about?

Ecoumène links my documentary commitment, linked to my practice of photographic and video images, and a more recent practice of live installation through which I have sought new formal writing and collective and interdisciplinary research methods. This return to investigation is a way to reconnect with the issues that matter to me and to get involved in them in a concrete way. The environmental commitment also continues a long research work, more theoretical, around the notion of “environment”. This “environment” is the ecological, technical and symbolic relationship we have with what surrounds us. These three aspects are jointly linked and indispensable to our development (individuation). If an imbalance occurs in this equation, the other terms are by extension impacted. In this sense, the ecological crisis cannot be limited to symptoms. These results reduce our understanding of the situation to a thin aspect of the problem. To understand it, it is a relational fabric that must be observed. The disappearance of the Malagasy forests revolts, but what is the colonial responsibility in the wood trade, which has deeply transformed the organization of society, know-how and territories? How does this economy impact traditional beliefs related to these spaces? Starting from the specificities of each individual story, of each place, the Ecoumene project confronts this complexity. It attempts to provide a new perspective on the formation of these knots and their current repercussions. Diving into the heart of these manufacturing situations, considering practical and emotional realities together, may allow us to identify new avenues of understanding and more global responses.

How was the technique of algebra born and what does it actually consist of?

Everything was born from a reflection on the image, on the way we represent the world. Photography freezes, immortalizes and frames. It touches me for its grip on reality, its phenomenon of chemical emergence, the experience of time that it crosses or the relationships that it weaves beyond its frame. It was necessary that this image becomes alive, that it forsakes illusions to assert itself as an observatory of the dynamics and processes in which our existences are inscribed. This process is my first scientific collaboration, the story of a meeting with Claude Yéprémian and the team “Cyanobacteria, Cyanotoxins and Environment” (National Museum of Natural History). The grain of the image is made up of a multitude of light-sensitive microorganisms. The cells organize themselves and develop according to the different lights of a negative, an image that I create and then project on the surface of the culture. The aggregation of cells, more or less strong, reveals the different green densities of the algaecide. Living, the image is linked to its environment which allows it to develop, transform or disappear. It is literally and figuratively an “environment” and reveals all its complexity. The choice of these micro-algae is also highly symbolic: as the first light sensors, they question our human perceptions and invite us to consider other sensibilities to the world. Markers of pollution and solutions to environmental imbalances, their adaptation and assimilation attest to our connection to the environment. Present in the water and in the air, they circulate on a global scale, linking remote areas to the places where technosciences are practiced. So many aspects that, on another scale, echo the realities of each proposed Ecoumenon.

How would you define your practice of portrait and landscape photography?

Joint. Portrait and landscape coexist in my documentary approach as much as in mesology, where each individual is associated with his environment. From then on, the portrait is an emotional state revealing its context; the landscape is an incarnation of subjectivities, of individual imprints. Each algebraic composition of Ecoumene seeks to restore the relationship that unites the individual to the space he inhabits. It is the result of a set of “samples” taken in situ: photographs, but also personal accounts, walks, meetings. The resulting form is a mixture of these physical and psychic experiences. During the confinement, I discovered Glenn Albrecht’s thinking and his notion of “solastalgia” which resonates strongly with this work. This term describes a state of anxiety, sorrow or helplessness felt by inhabitants deprived of the comfort of feeling “at home”, in the face of the environmental degradation of their living spaces. Each landscape portrait in Ecoumene explores this very notion of habitability, made precarious by gentrification, deforestation or river pollution. Despite the different territories, the transformation of the beloved place is always experienced as a quasi-physical wound for its inhabitants: the cutting of a tree in Vohibola is a form of amputation. The future Ecoumene on El Salto (Mexico) is based on the premise that breathing life back into a place, acting to preserve its human and non-human plurality, are gestures that preserve the environment as much as they heal in depth damaged human existences. More than ever, this project crosses the practices of portraiture and landscape, taking them well beyond a classical conception. The algae and the depolluting micro-algae that compose it, become the biological and symbolic support of a new habitat to be cultivated on this “dead zone”.

What is your environmental commitment as an artist and citizen?

These are choices and gestures that give rhythm to my daily life, but it is above all the particular place that I give to the living in my life and my practice: it is not only an external subject, but a concrete reality with which I live, I collaborate, that I experience as much as it experiences me. It is in this relationship that my environmental awareness and commitment is forged. It is also the one I try to transmit as an artist. To assume the modalities of expression of the living in our aseptic and more and more virtualized world, is not simple: it is in itself a political position. To the extent of an exhibition, the presence of a living work calls into question economic ends, ousts the notion of results, disrupts the sometimes rigid frameworks of institutional arrangements and demands new forms of emotional responsibility, based on attention and care.

The creation of collective research contexts is another way to advocate for the construction of plural visions. It seems to me that the artist has a key role to play in the circulation and connection between disciplines, ways of thinking and contexts that are too often isolated. Working with engineers and scientists, allowing them to glimpse a more emotional aspect of life is a way to influence the shape of future technologies. By its diffusion, Ecoumene V.2. facilitated the meeting between the activists of Vohibola and the new Malagasy minister in charge of ecology. Initiating and facilitating contact is another way to accelerate concrete repercussions. These approaches contribute, it seems to me, to forge new ecologies that will be necessary to better think tomorrow.

How do you imagine the world to come?

In the short term, it will be like the current and past crises: made of great ecological challenges that humans will have to face collectively. By ecology, I mean its broadest etymological acceptance which is that of habitats (eco). The limits that we are reaching affect our ways of living together biologically, socially, economically, symbolically, etc. When an industrialist produces food that they would not give to their child, do they collectively inhabit this world? For the future, I share Bruno Latour’s thought for whom the danger remains that “everything goes back to the way it was before”; that we initiate a revolution (rolling backwards) rather than an R-evolution. In order to be set in motion in a positive way, the world to come will have to consider as essential the logic of the living and the logic of the emotions.

Featured image: © Lia Giraud, Ecoumène V.2, algaegraphic detail

The COAL Prize 2025 dedicated to fresh water is a call to fight against the drying up of our sensitivities…

Created in 2019, the COAL Student Prize aims to support, through a residency in partnership with France’s Nature Reserves, students…

At a time when knowledge alone is no longer enough to motivate action, the Prix COAL 2024 calls for transformation…